So you’re a 23-year-old New Yorker and you want to re-invent rock music. You’ve met a Welsh avant-garde classical guy with a love for droning, atonal, challenging noise. You’ve got your mate from university on guitar, you swap between rhythm and lead, blending together perfectly. You’ve got a mate’s sister in to play drums – she pounds stark, stripped-down tribal beats heavy on the tom-tom and a bass drum on its side.

All you need now is the patronage of the world’s most controversial and exciting modern artist.

No doubt, Lou Reed, John Cale, Sterling Morrison and Mo Tucker would have made some incredible music without the sponsorship of Andy Warhol, but it is possible that it would never have seen the light of day. Without doubt, it was an allegiance that changed rock.

In December of 1965, The Velvet Underground played their first gig, at Summit High School in New Jersey. The music journo Al Aronowitz got them this booking; they allegedly stole his tape recorder by way of thanks. He said of them:

“They were just junkies, crooks, hustlers. Most of the musicians at that time came with all these high-minded ideals, but the Velvets were all full of shit. They were just hustlers.”

These young men and woman in a hurry got a two-week residency at the Café Bizarre in the Village, where there aggressive, discordant, outsider cool was not well received. The management expressly forbade them from playing ‘The Black Angel’s Death Song’ ever again. Naturally, they opened the next night’s set with it, and were fired.

Paul Morrissey, the film director and Warhol collaborator, was sure that there was money and exposure to be had from rock and roll and Warhol didn’t need any convincing once he saw the Velvets at Bizarre. This moody, brooding group blasting away, singing about S&M and smack in the incongruous surrounding of a pretty touristy bar with out-of-towners drinking shit with fruit in it: Warhol got it instantly.

He could see at once that there was no other band like the Velvet Underground in the world and saw immediately that association with them could guarantee exposure, coverage and outrage.

Warhol admired Reed’s energy, vision, single-mindedness; while the older man (Warhol was 36) provided to Reed not only the money, cachet and opportunity, but an approving, mentor-ish acceptance that he had never had as youngster. They both shared a mixture of vulnerability and teak-toughness.

Co-managing them with Morrissey, Warhol installed the Velvet Underground as a sort of house band at The Factory on 47th Street and opened up his chest of money, drugs, sex, glamour and fame.

However, Morrissey sensed that the cool-to-the-point-of-awkward stage presence of Reed might not be enough and persuaded them to use Warhol project Nico as a singer. The band were pretty vile to her, not rating her at all and resenting the imposition – they would play way loud over her vocals, turn her mikes off – and we have read that the Jewish Reed bore some sort of cultural antipathy to the German singer for the War, although not certain about that. There was a bit of a… love triangle isn’t quite the right phrase… “sex-power-control triangle?” going on with her and Cale and Reed, too.

Still, Cale eventually ended up doing a couple of solo records with her and they figured out that her vocals would be absolutely perfect for ‘All Tomorrow’s Parties’, ‘Femme Fatale’ and ‘I’ll Be Your Mirror’, which indeed they are.

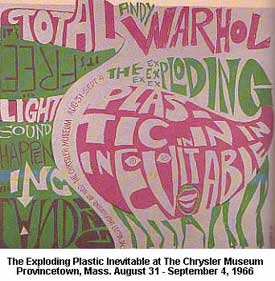

By the beginning of 1966, Warhol had the Velvets playing in his touring multimedia extravaganza The Exploding Plastic Inevitable. It was a magnificent vehicle for the band: they could play R and B, avant-garde, pop, weird soundscapes with warbling Nico… The diversity and range was deeply liberating.

By the beginning of 1966, Warhol had the Velvets playing in his touring multimedia extravaganza The Exploding Plastic Inevitable. It was a magnificent vehicle for the band: they could play R and B, avant-garde, pop, weird soundscapes with warbling Nico… The diversity and range was deeply liberating.

By the end of the year, they were recording their first album. Here, the influence ofWarhol was absolutely crucial. Nominally the producer, he would just sit at the board going “wow, that’s great” or whatever, but his word was law. He let the band just get on with whatever they wanted. As they were making the record without a label, or a deal, that meant they could do stuff that no label would have allowed – lyrically and in their disregard for structure on some songs. Warhol’s only significant creative contribution was, of course, the ‘peel slowly and see’ cover art.

Morrissey sold the completed album to Verve/MGM, and the band went back on the road with the Exploding Plastic Inevitable, certain that they were going to be huge – and rich. Morrissey has said that the label wanted Nico and Warhol and saw little or nothing in the band; what’s more, they had just released Frank Zappa’s ‘Freak Out’ and were not sure they could tackle another vastly ambitious, commercially unsound proposition. The album was held over until March 1967.

(When it finally did come out, there was a row over the back-cover photograph when a hard-up EPI actor whose image was used claimed a rights issue and demanded money. Rather than pay up, the label withdrew the album until it could re-issue, thus killing what very modest commercial momentum it had.)

During 1966, the Velvets were touring the West Coast with the Exploding Plastic Inevitable but Reed and Warhol became embroiled in a row over money. The band hated the West Coast sound and vibe – and the feeling was mutual. This is the beginnings of flower power and acid and you’ve got these amphetamine freak, angry, dark New Yorkers with their sneering and their droning electric violin and their songs about junk and violence and dirty nasty sex. They played a couple of iffy shows at the Fillmore and returned to New York, only for Reed to come down with hepatitis for six weeks.

While Reed was out, the band played a few gigs in Chicago that went down well, only fuelling the tension and power struggle within the band over Warhol’s influence and the presence of Nico.

The resentment simmered for months, and the poor commercial and critical reaction to the Velvet Underground And Nico only severed to heighten tensions. Finally the relationship broke down completely in the summer of 1967 when Warhol took Nico to a Velvets show in Boston and the band refused to let her on stage.

Finally the relationship broke down completely in the summer of 1967 when Warhol took Nico to a Velvets show in Boston and the band refused to let her on stage.

She said: “Everybody wanted to be the star. Of course Lou always was. But the newspapers came to me all the time. That’s how I got fired - he couldn’t take that anymore. He fired me.”

Warhol and the band split immediately, Warhol letting Reed out of the contract with no argument. The band would go on to make the astonishing White Light / White Heat – a masterpiece of aggression and dissonance, a kind of anti-music in parts – the coming September (1967). Their Warhol era was over, but the record they made together will live forever.

No comments:

Post a Comment