Davy Graham, who died last December, was a guitarist who influencedPaul Simon, Jimmy Page,Ray Davies, John Martyn,Johnny Marr and Graham Coxon.

Davy Graham, who died last December, was a guitarist who influencedPaul Simon, Jimmy Page,Ray Davies, John Martyn,Johnny Marr and Graham Coxon.

He is not anything like as commercially successful as any of these acolytes, yet his techniques and vision helped to shape modern music and he was a revered figure to all of these players, and to countless other guitarists.

Born (1940) in Leicester to a Gaelic teacher dad from the Isle Of Skye and a Guyanese mother, he grew up in London’s Westbourne Grove, he learned to play early Elvis and songs by Lonnie Doneghan. He left school at 18 to busk around Southern Europe and North Africa, engendering a passion for Moroccan music that would flavour his career.

He returned to London to play in the coffee houses of Soho, learning from folk players like Rambling Jack Elliott, and was featured in Ken Russell’s 1959 documentary ‘Hound Dogs and Bach Addicts: The Guitar Craze’, in which he played an accomplished and elaborate version of ‘Cry Me A River’.

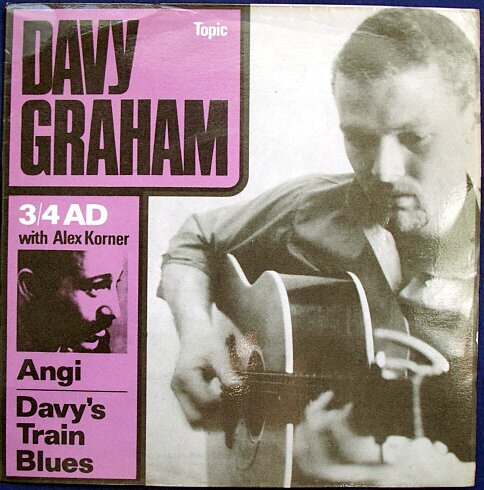

At 19, Graham wrote his most famous piece, ‘Anji’, named for a girlfriend. There cannot be an acoustic guitarist of any note who has not learned and played it. Famous versions have included those by Paul Simon; Bert Jansch of Pentagle; and Chicken Shack. The tune was the highlight of Davy’s 1962 debut EP 3/4 AD – a record which won him the immediate acclaim of his peers.

He was at this time playing with John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers and Alexis Korner’s Blues Incorporated, but he was at heart a solo artist. Ray Daviesremembers him as having “an incredible physical presence” – he had an upright, almost military bearing and a rather magnificent moustache – and said that he was “the greatest blues player I ever saw, apart from Big Bill Broonzy”. Davy also introduced the idea of tuning the guitar DADGAD, the Celtic influence from his father’s culture, that allowed more freedom with the melody and the top strings while keeping harmony in the bass, mimicking the drone of pipes.

He was at this time playing with John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers and Alexis Korner’s Blues Incorporated, but he was at heart a solo artist. Ray Daviesremembers him as having “an incredible physical presence” – he had an upright, almost military bearing and a rather magnificent moustache – and said that he was “the greatest blues player I ever saw, apart from Big Bill Broonzy”. Davy also introduced the idea of tuning the guitar DADGAD, the Celtic influence from his father’s culture, that allowed more freedom with the melody and the top strings while keeping harmony in the bass, mimicking the drone of pipes.

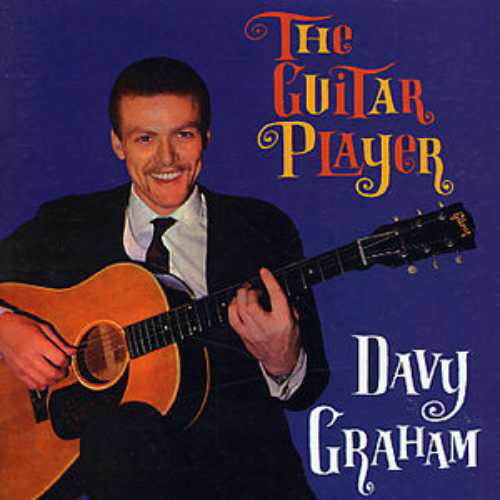

Mastery of folk and blues was not enough for this eclectic, hungry innovator, though – he became fascinated by Miles Davis and Ornette Coleman, incorporating their themes and styles into his work. He released the 1963 debut LP The Guitar Player, then 1964s Folk, Blues And Beyond and then Midnight Man (1966).

Folk, Blues And Beyond melded folk and traditional playing along with Moroccan themes into a wonderful, dazzling brew, while Midnight Man added the vocals of folker Shirley Collins to the flavours of Theolonius Monk. Davy was so obsessed with the jazz greats that he adopted another of their themes: heroin use. Long-time friend and colleague Martin Carthy said:

Folk, Blues And Beyond melded folk and traditional playing along with Moroccan themes into a wonderful, dazzling brew, while Midnight Man added the vocals of folker Shirley Collins to the flavours of Theolonius Monk. Davy was so obsessed with the jazz greats that he adopted another of their themes: heroin use. Long-time friend and colleague Martin Carthy said:

“He was a lovely man, but he was in thrall to jazz players like Charlie Parker, and the whole drug culture. And though there was very little heroin on the British folk scene, he deliberately became a junkie.”

The Sixties saw Davy travelling the world, incorporating diverse influences into his work. It’s said that he stopped in Bombay en route to Australia and decided to spend six months wandering round India rather than continue Down Under. He added Indian raga music to his blues – check out the brilliant 1969 album Hat – and there was simply no limit to his imagination or talent for interpretation, be it classical or Moroccan or Celtic or Eastern European folk, he would work it into his playing. The genre of World Music could not exist without him.

But the drugs and the lifestyle began to tell and he became reclusive, burned out, by the end of the decade a la Greeny or Syd. He played few public appearances after the Sixties and immersed himself in the study of languages – Arabic, Turkish, Gaelic – and learning the oud (an Arabic lute), his work with which can be heard on 1979’s Dance For Two People. He married Holly Gwinn in the late Sixties, but he and his wife separated after recording the album Godington Boundary together in 1970. He did a lot of work with mental health charities.

But the drugs and the lifestyle began to tell and he became reclusive, burned out, by the end of the decade a la Greeny or Syd. He played few public appearances after the Sixties and immersed himself in the study of languages – Arabic, Turkish, Gaelic – and learning the oud (an Arabic lute), his work with which can be heard on 1979’s Dance For Two People. He married Holly Gwinn in the late Sixties, but he and his wife separated after recording the album Godington Boundary together in 1970. He did a lot of work with mental health charities.

He gave a few small performances in later life, and on his day he was still utterly brilliant. Writes Robin Deneslow of one London gig in 2006:

“He came on looking like a cool veteran cowboy, in black hat and dark glasses, and played a set that included a Romanian dance tune, Irish pipe tunes and songs from South Africa, before announcing, “A bit of Bach, I think”, and being greeted with as many cheers as when he launched into a blues.”

Davy was a relentless innovator with an insatiable appetite for great music of all forms, and he had the talent and soul to express that with glorious, beautiful playing.

A true hero.

No comments:

Post a Comment