Roy Harper

His admirers and collaborators have included Jimmy Page, Robert Plant, Dave Gilmour, Ian Anderson, Paul McCartney andKate Bush. His fingerpicking acoustic style is as recognisable as Jimmy Page’s bow. He’s written some of the most beautiful and uniquely English electric folk. He has recorded without a break of any length of time for more than 40 years. He has attracted controversy for attacking such diverse targets as Islam and the food at Watford Gap service station. He has never compromised his art for money and has described himself as “the longest running underground act in the world”. Roy Harper is an underappreciated genius.

Brought up in Rusholme by a stepmother who was a devout Jehovah’s Witness – helping to formula Roy’s lifelong disgust for organised religion – his was not a happy childhood, apart from the long hours spent playing skiffle music with his older brother Davey. He went into the RAF at 15, hated it, feigned madness and was “treated” with electroconvulsive shock therapy.

R oy busked around Europe in the early sixties before finding his way to London where he began playing on the folk circuit. By 1964 he had a residence at the influential folk club Les Cousins. He saw himself as a poet, rather than a songwriter; music was a way to deliver the words.

oy busked around Europe in the early sixties before finding his way to London where he began playing on the folk circuit. By 1964 he had a residence at the influential folk club Les Cousins. He saw himself as a poet, rather than a songwriter; music was a way to deliver the words.

He was signed by little Strike Records for his debut album, 1966’s Sophisticated Beggar, which in many ways set the template for his career: the lovely guitar work, the idiosyncratic lyrics, the rockristocracy guests – Ritchie Blackmoreplayed some guitar – the critical appreciation and the lack of commercial success. Still, it was well enough received for him to be signed up by Columbia, for whom he released Come Out Fighting Genghis Smith, a lyrically challenging and often apparently deliberately obtuse effort. The 11-minute ‘Circle’ showed that he was absolutely not to be contained by the prescription of what a folk rock song could or should be. Playing in various free concerts in Hyde Park, by 1968 Harper had attracted a small but committed following, but 1969’s Folkjokeopus was again a commercial miss, but featured the brilliantly weird 17-minute ‘McGoohan’s Blues’ about the star of the cult TV series The Prisoner. Even at this early stage of his career, Roy knew that his path would be a lonely one.

Playing in various free concerts in Hyde Park, by 1968 Harper had attracted a small but committed following, but 1969’s Folkjokeopus was again a commercial miss, but featured the brilliantly weird 17-minute ‘McGoohan’s Blues’ about the star of the cult TV series The Prisoner. Even at this early stage of his career, Roy knew that his path would be a lonely one.

“By the time I was 25 and beginning to get somewhere in music I thought that I could crack through, I thought I could break through the big eggshell and get inside, but as time went on it became increasingly obvious that someone like me with the material I've got that is too deep for normal consumption, for mass consumption, was never going to get through,” he said.

1970 was a bit year for Roy: he signed for Harvest, the EMI subsidiary, and went on his first tour of the US. His fourth album, Flat Baroque And Berserk showed his appetite for difficult, controversial themes with the somewhat bizarre ‘I Hate The White Man’ and a cool, tripping production involving plenty of wah-wah. It also featured The Nice on ‘Hell’s Angels’, the album’s more rocky, less folky closing number.

At the 1970 Bath Festival, Led Zep bigged Roy up with a version of ‘Shake Em On Down’ which was reworked onto Led Zeppelin III as ‘Hats Off To (Roy) Harper’. Roy has had a career-long friendship and association with both Page and Plant, with Jimmy appearing on Roy’s next album, Stormcock, under the name of S. Flavius Mercurius.

Stormcock, containing four long songs, is probably Roy’s finest hour. ‘The Same Old Rock’ is a broadside at organised religion featuring a scorching solo by Page; ‘Me And My Woman’ is a sweeping orchestral powerhouse; ‘One Man Rock And Roll Band’ is just lovely. And it sums him up rather well: it’s like a solo Pink Floyd or something, this: ambitious yet intimate.

1972 saw Roy nearly die from a blood disorder. He released Lifemask the following year, some of whose songs featured in the film Made, an intense drama about the relationship between a single mum, and insecure rock singer and a lapsing Priest that puts the boot into Christianity. Lifemask also sees Roy sticking it to Apartheid on ‘South Africa’ and features guitar from Jimmy Page.

1974’s live album § From The Archives Of Oblivion is, along with Stormcock, the one we would recommend if you want to get a flavour of Roy’s early career. Some of it was recorded from a live gig at London’s Rainbow Theatre on Valentine’s Day 1974 featuring Page on guitar, Keith Moon on drums, Ronnie Lane on bass and The Jeff Beck Group’s Max Middleton on keys. There’s also a beautiful studio track ‘Twelve Hours Of Sunset’ with Ian Anderson on the flute. 1974 had also seen Roy open for Led Zep on a US tour, and Page is against on brilliant form with the solo on ‘Male Chauvinist Pig Blues’ from 1974’s Valentine album.

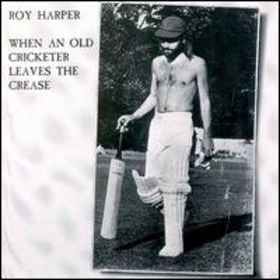

In 1975, Roy sang lead vocal’s on the Floyd’s ‘Have A Cigar’ and Dave Gilmour reciprocated by appearing on Roy’s next, album, titled HQ in the UK and, for the US, When An Old Cricketer Leaves The Crease. The ‘When An Old…’ single, beguiling and melancholic, remains Roy’s biggest hit. Also playing on that album was Roy’s short-lived backing band, Trigger, featuring the prodigious talents of Bill Bruford and Chris Spedding, whileJohn Paul Jones and Dave Gilmour also contribute. We love the cover art of this and admire the wilful anti-commercialism of titling the AMERICAN version with a cricket theme.

In 1975, Roy sang lead vocal’s on the Floyd’s ‘Have A Cigar’ and Dave Gilmour reciprocated by appearing on Roy’s next, album, titled HQ in the UK and, for the US, When An Old Cricketer Leaves The Crease. The ‘When An Old…’ single, beguiling and melancholic, remains Roy’s biggest hit. Also playing on that album was Roy’s short-lived backing band, Trigger, featuring the prodigious talents of Bill Bruford and Chris Spedding, whileJohn Paul Jones and Dave Gilmour also contribute. We love the cover art of this and admire the wilful anti-commercialism of titling the AMERICAN version with a cricket theme.

Following this album came Bullinamingvase (US title: One Of Those Days In England’, another cracking record and chock-full of angry, lyrically scorching attacks on modern life, mind-rotting government and the food at service stations: “Watford Gap, Watford Gap, a plate of grease and a load of crap.” The owners complained and the album was withdrawn and re-released without it!Paul McCartney and Linda provided backing vocals for the single ‘One of Those Days In England’.

Following this album came Bullinamingvase (US title: One Of Those Days In England’, another cracking record and chock-full of angry, lyrically scorching attacks on modern life, mind-rotting government and the food at service stations: “Watford Gap, Watford Gap, a plate of grease and a load of crap.” The owners complained and the album was withdrawn and re-released without it!Paul McCartney and Linda provided backing vocals for the single ‘One of Those Days In England’.

But just when it seemed that Roy might be starting to sell more heavily, a row with EMI records forced the shelving of what would have been his next album, Commercial Break. As it turned out, his last record with EMI would be the next one, 1980’s The Unknown Solider, the last Roy recorded at Abbey Road. He duets with Kate Bush on ‘Yes’, and Gilmour provides strong contributions on that track and on ‘Short And Sweet’, but this album marked the beginning of a probably misguided new direction in production – synths, needless over-elaboration – that continued with 1982’s Work Of Heart, which is most remarkable for being the first post-EMI record that Harper made, on the label he set up himself. He has said: “There is no doubt in my own mind that the early eighties were the nadir of my life in music.”

The Unknown Solider, the last Roy recorded at Abbey Road. He duets with Kate Bush on ‘Yes’, and Gilmour provides strong contributions on that track and on ‘Short And Sweet’, but this album marked the beginning of a probably misguided new direction in production – synths, needless over-elaboration – that continued with 1982’s Work Of Heart, which is most remarkable for being the first post-EMI record that Harper made, on the label he set up himself. He has said: “There is no doubt in my own mind that the early eighties were the nadir of my life in music.”

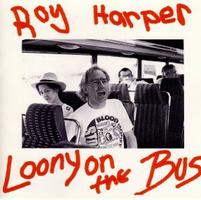

Harper and Jimmy Page amused themselves with low-key acoustic tours of the UK under such names as The MacGregors and Themselves, before releasing the 1984 album Whatever Happened To Jugula, with Page given full joint-billing. Nihilistic, slightly terrifying and graced at one point by a recording of Roy going for a piss, it is… well, it’s not for everyone. A couple of so-so live records and the eventual release of Commercial Break, now under the name Loony On The Bus wrapped up the decade.

Harper and Jimmy Page amused themselves with low-key acoustic tours of the UK under such names as The MacGregors and Themselves, before releasing the 1984 album Whatever Happened To Jugula, with Page given full joint-billing. Nihilistic, slightly terrifying and graced at one point by a recording of Roy going for a piss, it is… well, it’s not for everyone. A couple of so-so live records and the eventual release of Commercial Break, now under the name Loony On The Bus wrapped up the decade.

But you can’t keep a good man down, an Harper was right back in form with 1990’s Once, which dealt mainly with the fall of Communism. The stand-out is probably ‘Berliners’ with Gilmour.  Roy showed it wasn’t just Christians that he had it in for with ‘The Black Cloud Of Islam’ with its lyrics:

Roy showed it wasn’t just Christians that he had it in for with ‘The Black Cloud Of Islam’ with its lyrics:

“You can put a lead bullet clean through this guitar, ’cause I’m not overjoyed at the story so far. Sharing the world with the nutters of god is as good as being six feet under the sod.”

He followed the album with one of his very best, the almost raw and sad Death Or Glory? (1992) that was inspired by his wife leaving him. It’s stripped-down, acoustic sound is classic Roy. His son Nick plays on ‘The Tallest Tree’. It’s not all misery: ‘Evening Star’ is a lovely number written for Robert Plant’s daughter on the occasion of her wedding, but this is powerful, bitter stuff in the main.  An excellent record, though, and the one we would recommend after Stormcock and Flashes From The Archives Of Oblivion.

An excellent record, though, and the one we would recommend after Stormcock and Flashes From The Archives Of Oblivion.

Throughout the 1990s and beyond, Roy has released a variety of live performances – notably the BBC tapes – and back catalogue material on his own Science Friction label. In 1998, he made the cracking LP The Dream Society, with son Nick playing a terrific acoustic guitar on opener ‘Songs Of Love’. It closes with the 15-minute ‘These Fifty Years’, which is as soaring and rich as anything Roy has done.

The same could be said of 2000’s The Green Man, a magnificent record that thematically and stylistically evokes the classic Stormcock while seemingly totally of the moment. He mixed and engineered this himself, alone: it’s an incredibly personal record and one that feels a privilege to listen to.

The same could be said of 2000’s The Green Man, a magnificent record that thematically and stylistically evokes the classic Stormcock while seemingly totally of the moment. He mixed and engineered this himself, alone: it’s an incredibly personal record and one that feels a privilege to listen to.

Roy has recently retired from touring to focus on writing and also on compiling a career retrospective. He is one of our greatest songwriters, a truly unique talent who has been underappreciated in his own lifetime, but we are certain that in years to come he will be regarded as a true legend of British rock.

No comments:

Post a Comment